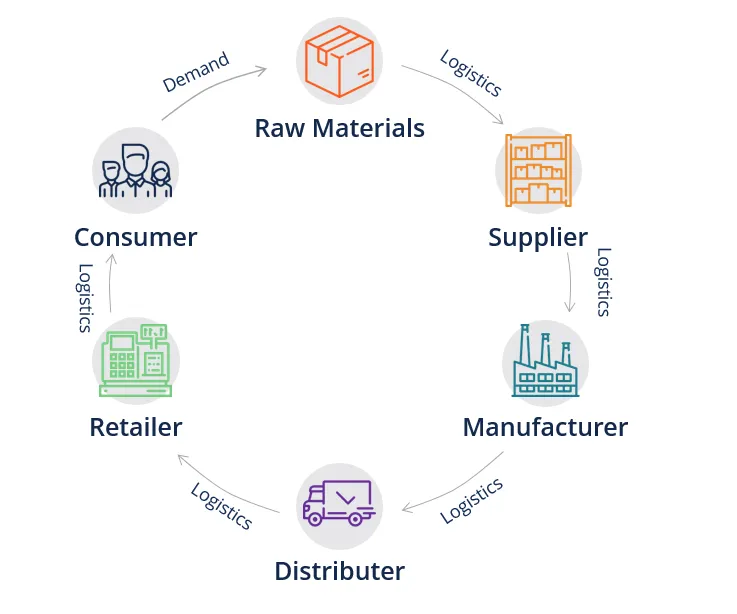

A supply chain is a series of processes, activities and a network of people that help to make and move a product from start to finish (consumption). Supply chains are often complex with various stages of production happening in different countries, controlled by different suppliers. Here is a simple diagram by the Corporate Finance Institute to explain the process:

In simple terms, there is the supply (raw materials for manufacturing), manufacturing (building, assembling, converting, or furnishing raw materials into finished products), distribution (ensuring products reach consumers through organised networks of transporters, warehouses, and retailers) and consumption (the customers).

Here is a breakdown of the global supply chain for chocolate:

- Cocoa – West Africa, Central/South America, and parts of Asia.

- Nuts – worldwide (depending on the type of nut).

- Sugar – Brazil (primarily), India, and China

- Milk – United States.

- Corn Syrup – United States, Europe, Brazil, and Mexico.

- Vanilla – Madagascar, Indonesia, China, and Mexico.

- Aluminium Foil – West Indies, North America, and Australia.

Exploitation in Supply Chains:

At any point in the supply chain of a product, there is a risk of slavery being used. This means that the clothes we wear, foods we eat, technology we use – the goods and services we consume on a day-to-day basis could have been produced using forms of modern slavery.

With greater demand, businesses are always looking for cheaper sources of labour. There are over 16 million people exploited in the private sector, linked to the supply chains of the international businesses supplying our goods and services (Anti-Slavery International). Approximately 60% of forced labour is associated with manufacturing supply chains.

Additionally, supply chains can often be extensive and complex. This means that it is difficult for a business to oversee who is working where and under what conditions. Moreover, the globalisation of supply chains has added to the challenging nature of ensuring that suppliers are enforcing the same measures.

The agricultural, fast fashion and technological industries are at the highest risk of using forms of slavery in their supply chains.

Agricultural Industry:

According to the International Labour Organisation, agriculture, fishery and forestry are the sectors with the fourth highest proportion of victims of forced labour worldwide.

Victims in the agricultural sector in Europe are often lured by the false promise of a job by traffickers. Many agricultural “workers” are enslaved through debt bondage (a form of slavery) to repay debts. The cocoa industry alone has over 2.1 million children working in their supply chains!

In the coffee industry, children as young as six work ten hours a day and are exposed to the many health and safety hazards. The coffee harvesting process involves dangers from high levels of sun exposure and injuries, to poisoning from contact with agrochemicals.

Fast Fashion:

Forced labour is present in the fashion industry, from child cotton pickers in Uzbekistan, held in debt bondage by their employers to those who are coerced into factory labour in India and Bangladesh. Victims are forced to live a life of fear and violence, exploited to work hours on end to meet the demands of corporate consumerism.

G20 countries imported $127 billion fashion garments identified as at-risk products of modern slavery (2019). Fast fashion brands including H&M, Primark, Zara, T.J. Max and Nike all profit off of the exploitation of people.

Globally, the COVID-19 outbreak has threatened the livelihoods of garment workers too. In Bangladesh for example, after 100 factories closed, over 4 million garment workers became vulnerable to exploitation due to loss of their steady income.

Technological Industries:

There is a risk of forced labour in the electronics industry in China, Thailand, Malaysia, DR Congo, the Philippines, and Indonesia. Electronic brands such as Apple, Samsung and Microsoft engage in supply chain slavery.

Risks are often associated with migrant workers who may incur large debts in their pursuit of employment and may face debt bondage. They can be stripped of passports and work documents or held in a place of employment against their will. Children are forced to mine cobalt for use in the latest mobile phone and people in factories are forced to assemble electronics.

However, new technologies can assist companies to follow ethical practices in their supply chain. Potential solutions to this problem include the use of blockchain and artificial intelligence.

Governments Must Take Action:

Governments must introduce import controls on goods produced using forced labour.

This should increase supply chain transparency, will ensure that companies are held accountable, enforce appropriate sanctions and produce zero-tolerance policies to forced labour.

Governments must do more to take effective and coordinated action. Existing policies aimed at tackling forced labour in supply chains have been described as inefficient and ‘toothless’. We must do better – governments must act urgently.

Furthermore, governments must coordinate, internationally, to implement complementary policies to import controls. For example, mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence legislation to effectively tackle forced labour in global supply chains.

Policies should be directed at preventing the root causes enabling forced labour in the first place (poverty, gender inequality, worker discrimination, lack of worker representation and legal protection etc).

All of these measures to tackle forced labour need to be secured in trade agreement, legislative and development frameworks.